Linear Circuit Analyis (Webbook)

1. Introduction

2. Basic Concepts

- Charge, current, and voltage

- Power and energy

- Linear circuits

- Linear components

- Nodes and loops

- Series and parallel

- R, L & C combinations

- V & I combinations

3. Simple Circuits

- Ohm's law

- Kirchhoff's current law

- Kirchhoff's voltage law

- Single loop circuits

- Single node-pair circuits

- Voltage division

- Current division

4. Nodal and Mesh Analysis

5. Additional Analysis Techniques

- Superposition

- Source transformation

- The $V_{test}/I_{test}$ method

- Norton equivalent

- Thévenin equivalent

- Max power transfer

6. AC Analysis

7. Magnetically Coupled Circuits

8. Polyphase Systems

9. Operational Amplifiers

10. Laplace Transforms

11. Time-Dependent Circuits

- Introduction

- Inductors and capacitors

- First-order transients

- Nodal analysis

- Mesh analysis

- Laplace transforms

- Additional techniques

12. Two-Port Networks

Appendix

1. Introduction

1.1 Preface

Linear Circuit Analysis is a core course in electrical engineering that most undergraduate students need to take in the first year of their program. In fact, the course covers topics that are so fundamental that, most often, students from other engineering areas such as computer, industrial, power, or manufacturing engineering also need to take it as an introduction to electrical engineering.

This webbook is designed to be used by students to learn linear circuits while solving problems on the CircuitsU website; instructors can use the website to teach linear circuits without the need for other textbooks. This webbook and the problems generated by CircuitsU, cover most topics in the Linear Circuit Analysis course taught in undergraduate programs in the U.S. and is organized relatively similar to the existing textbooks on linear circuits.

The webbook is slightly different from other books or materials in linear circuits that you can find online. First, the webbook is written in a concise manner to make students spend a minimum amount of time learning the different topics on linear circuits and be able to spend more time practicing problems on their own. For this reason, just by browsing the pages of the webbook might not be sufficient to master all the topics on linear circuits (like a regular textbook is supposed to do) and students should first review the Examples of Solved Problems sections that appears at the end of most sections and then practice using the Practice Problems sections.

Second, the problems and examples that appear at the end of each section are generated randomly when the page is loaded, so students can look over and practice as many problems as they want. Due to the relatively large computational cost required to genearate random problems, you need to be logged in order to take advantage of the full set of examples and problems at the end of the sections.

Have fun!

1.2 Topics Covered in CircuitsU

Below is the list of topics for which CircuitsU can generate random problems, organized in chapters. The instructor can build homework assignments covering problems from different chapters (for instance, to design a midterm or a final exam). In addition, the instructor can change the type, difficulty, and number of homework problems that the site will generate in each homework assignment.

Chapters 1 and 2 provide an introduction to electric components, circuit diagrams, and concepts such as charge, current, voltage, energy and power in electric circuits. Chapters 3-10 focus on DC circuits; chapters 11-21 focus on AC circuits; chapters 22-26 focus on Laplace transforms and first and second-order transient circuits. These homework assignments cover most of the topics that are usually covered in a college-level, introductory course on linear circuit analysis. For instance, if the Linear Circuit Analysis course is taught as a:

- year-long course sequence: most topics could be covered throughout the course

- two-semester course sequence: chapters 1-16 could be offered during the first semester and chapters 17-26 are offered during the second semester

- three-quarter course sequence: chapters 1-10 could be offered during the first quarter, chapters 11-17 are offered during the second quarter, and chapters 18-26 are offered in the third quarter

Types of Problems

- General problems, in which students need to answer simple questions such as identifing different components in a circuit, or series and parallel connections.

- Numerical problems, (ℕ), in which the known variables in the problem are given numerically and students need to compute the shought variable or variables numerically.

- Analytical problems, (Ⓐ), in which the known variables are given symbolically and the students need to compute the analytically.

- Design problems, (ⅅ), in which students need to compute specific elements in a circuit in order for some conditions to be satisfied (e.g. what are the values of specific resistors such that the gain of an amplifier to be equal to 10).

- Graphical problems, (G), in which students need to extract information from a graphic and compute different quantities (e.g. compute the current going through a capacitor if the charge is given graphically as function of time).

1. Nodes and loops, series and parallel connections

- Identify resistors, capacitors, inductors, voltage and current sources in electric circuit diagrams

- Identify nodes and loops in electric circuits

- Identify series and parallel connections

2. Charge, current, voltage, energy, power

- Evaluate the charge going through a component

- Evaluate the energy generated or dissipated by a component

- Compute the instantaneous current, voltage, and power generated or dissipated

2. R, L, C combinations

- Compute the equivalent resistance of a network

- Compute the equivalent capacitance/inductance of a network of capacitors/inductors

- Compute the charge, current and voltage as a function of time in capacitors and inductors

- Compute the energy stored by capacitors and inductors

3. Simple circuits

- Use KVL and KCL to analyze single loop and single node-pair circuits

- Use voltage and current division to solve simple circuits

- Compute the power generated/dissipated by a component

4. DC nodal analysis

- Write and solve the system of nodal equations in DC circuits

- Compute DC currents, voltages, and powers using nodal analysis

- Use nodal analysis to solve design problems

5. DC mesh analysis

- Write and solve the system of mesh equations in DC circuits

- Compute DC currents, voltages, and powers using mesh analysis

- Use mesh analysis to solve design problems

6. DC superposition

- Analyze DC circuits using the method of superposition

7. DC source transformation

- Use source transformation to compute currents, voltages and powers in DC circuits

8. DC Norton and Thévenin equivalent circuits

- Compute the Norton and Thévenin equivalent circuits of a DC network

- Simplify DC circuits by making successive source transformations

9. Operational amplifiers (DC)

- Analyze DC circuits with ideal OpAmps

- Analyze DC circuits with real OpAmps (in which $A$, $R_{in}$ and/or $R_{out}$ are nonzero and finite

10. Impedance simplification (AC)

- Compute the equivalent (complex) impedance of a network containing resistors, capacitors and inductors

11. AC nodal analysis

- Write and solve the system of nodal equations in AC circuits

- Compute AC currents and voltages using nodal analysis

12. AC mesh analysis

- Write and solve the system of mesh equations in AC circuits

- Compute AC currents and voltages using mesh analysis

13. AC superposition

- Analyze AC circuits using the method of superposition

14. AC source transformation

- Use source transformation to compute currents and voltages in AC circuits

15. AC Norton and Thévenin equivalent circuits

- Compute the Norton and Thévenin equivalent circuits of an AC network

- Simplify AC circuits by making successive source transformations

16. Operational amplifiers (AC)

- Analyze AC circuits with ideal OpAmps

17. AC power analysis

- Calculate instantaneous and average power in AC circuits

- Calculate real power, reactive power, complex power, and power factor in AC circuits

- Find maximum power transfer

18. Magnetically coupled networks

- Analyze AC circuits with magnetically coupled inductors

- Analyze AC circuits with ideal transformers (nodal analysis, mesh analysis, transformer elimination)

19. Polyphase circuits

- Analyze two-phase and three-phase circuits

- Use delta-wye transformations

- Compute instantaneous and total power, and pf

20. Two-port networks

- Calculate the admittance ($y$), impedance ($z$), hybrid ($h$ and $g$), and transmission ($t$ and $t'$) parameters for two-port networks

- Convert from one type of network parameters to another type (e.g. $y$-parameters to $z$-parameters,...)

21. Frequency selective circuits

- Compute voltage gain ($G_v$), current gain ($G_i$), transimpedance ($Z$), and transadmittance ($Y$) of AC filters

- Compute the transfer function from a given Bode plot

- Draw the straight-line Bode magnitude plot for a specific transfer function

- Compute the resonant frequency, bandwidth, quality factor, half-power frequencies etc. in RLC circuits

22. Laplace transforms

- Compute the direct and inverse Laplace transforms of different functions using the linearity of Laplace transforms, time-shifting, frequency shifting, etc.

23. Laplace impedance simplification

- Transform a circuit from time domain to s-domain

- Compute the impedance of a circuit in the s-domain

24. First-order transient circuits

-

Compute time-dependent currents and voltages in first-order transient circuits using:

1) the time relaxation approach (aka step-by-step approach)

2) the Laplace transform method

3) the method of integro-differential equations (for nodal and mesh analysis)

25. Second-order transient circuits

-

Compute time-dependent currents and voltages in second-order transient circuits using:

1) the Laplace transform method

2) the method of integro-differential equations (nodal and mesh) analysis

26. Other applications of Laplace transforms

- Superposition in the s-domain

- Source transformation in the s-domain

- Norton and Thévenin equivalent circuits in the s-domain

- Higher-order transient circuits

1.3 Assignments by chapter

Below are the recommended assignments (HW1-HW32) that are generated by default when the instructor creates a new Linear Circuit Analysis course and choses Selected HW assignments by chapter (37 assignments).

| Module number | HW namea | HW numberb | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Module 1 | Series/Parallel | HW 1 | Identify R, L, C, voltage and current sources, nodes, and loops, series and parallel connections. |

| Module 2 | Charge, current, voltage, energy and power | HW 2 | Compute charge, currents, voltages, energy and power in single source-load networks. |

| Module 3 | Resistor simplification | HW 3 | Simplify a network of resistors using series and parallel transformations. |

| Module 4 | Simple circuits | HW 4 | Compute currents, voltages, and powers (dissipated and generated) in simple networks using KVL, KCL, current and voltage division. |

| Module 5 | DC nodal analysis (eqs.) | HW 5 | Write the system of nodal analysis equations (but do not solve it). |

| Module 6 | DC nodal analysis (num.) | HW 6 | Write and solve the system of nodal analysis equations to compute currents, voltages and powers. |

| Module 7 | DC mesh analysis (eqs.) | HW 7 | Write the system of mesh analysis equations (but do not solve it). |

| Module 8 | DC mesh analysis (num.) | HW 8 | Write and solve the system of mesh analysis equations to compute currents, voltages and powers. |

| Module 9 | DC superposition | HW 9 | Use the superposition method to compute currents and voltages in electric networks. |

| Module 10 | DC source transformation | HW 10 | Simplify a circuit using successive source transformations. |

| Module 11 | DC Norton/Thévenin | HW 11 | Compute the Norton and Thévenin equivalent circuits or DC networks. |

| Module 12 | DC OpAmps | HW 12 | Analyze circuits containing one or more operational amplifiers. |

| Module 14 | Inductors and capacitors | HW 14 | Current, voltage, charge, power and energy in inductors and capacitors; simplify networks of capacitors and inductors using series and parallel transformations. |

| Module 14 | Impedance simplification | HW 14 | Compute the effective impedance of an AC network of R, L, and C using series and parallel combinations. |

| Module 15 | AC nodal analysis | HW 15 | Compute currents and voltages in AC circuits using nodal analysis. |

| Module 16 | AC mesh analysis | HW 16 | Compute currents and voltages in AC circuits using mesh analysis. |

| Module 17 | AC superposition | HW 17 | Use the superposition method to compute currents and voltages in AC circuits. |

| Module 18 | AC source transformation | HW 18 | Simplify an AC circuit using successive source transformations. |

| Module 19 | AC Norton/Thévenin | HW 19 | Compute the Norton and Thévenin equivalent circuits or AC networks. |

| Module 20 | AC coupled inductors | HW 20 | Compute currents and voltages in AC networks containing coupled inductors using mesh analysis. |

| Module 21 | AC ideal transformers | HW 21 | Compute currents and voltages in AC networks containing ideal transformers using nodal or mesh analysis, or the transformer elimination method. |

| Module 22 | Polyphase circuits | HW 22 | Three-phase circuits, delta-wye transformations, power, and power factor. |

| Module 23 | RLC resonant circuits | HW 23 | Compute the resonant frequency, the quality factor, the band width, and half-power frequencies in RLC series and parallel circuits. |

| Module 24 | AC OpAmps | HW 24 | Single OpAmp inverters and followers containing AC sources, resistors, inductors, and capacitors. |

| Module 25 | AC power | HW 25 | Compute real power, reactive power, complex power, and power factor in AC circuits; power factor correction methods. |

| Module 26 | AC maximum power transfer | HW 26 | Compute maximum power transferred in AC circuits; AC power factor correction. |

| Module 27 | First-order transient circuits | HW 27 | Use the time relaxation approach to compute currents and voltages in first-order transient circuits. |

| Module 28 | Nodal analysis using ODEs (eqs.) | HW 28 | Write the system of nodal analysis ODEs for first, second and higher-order transient circuits (zero and non-zero initial conditions). |

| Module 29 | Mesh analysis using ODEs (eqs.) | HW 29 | Write the system of mesh analysis ODEs for first, second and higher-order transient circuits (zero and non-zero initial conditions). |

| Module 30 | Bode plots | HW 30 | Derive the transfer function from the Bode magnitude plot and draw the Bode magnitude plot of a transfer function. |

| Module 31 | Laplace transforms | HW 31 | Compute the direct Laplace transform of various functions. |

| Module 32 | Inverse Laplace transforms | HW 32 | Compute the inverse Laplace transform of various functions. |

| Module 33 | Laplace impedance simplification | HW 33 | Transform a circuit to s-domain and compute its equivalent s-domain impedance. |

| Module 34 | Laplace nodal analysis (num.) | HW 34 | Convert circuits to s-domain, then write and solve the system of nodal analysis equations for first and second-order transient circuits (zero initial conditions). |

| Module 35 | Laplace mesh analysis (num.) | HW 35 | Convert circuits to s-domain, then write and solve the system of mesh analysis equations for first and second-order transient circuits (zero initial conditions). |

| Module 36 | Source transformation in s-domain (num.) | HW 36 | Source transformations, Norton/Thévenin equivalent circuits and superposition in the s-domain (zero initial conditions). |

| Module 37 | Two-port networks | HW 37 | Compute y, z, h, and t parameters of DC and AC two-port networks. |

bThe default homework name when a new course is generated in CircuitsU.

cThe default homework number when a new course is generated in CircuitsU.

1.4 2-Semester Courseplan

Semester 1

Below are the default assignments (HW1-HW19) that are generated when the instructor creates a new Linear Circuit Analysis course and choses Semester 1 in a 2-semester course. The table shows the proposed due dates for each HW set but each instructor can set his or her own time schedule. The instructor can also re-organize the content and change the type, difficulty, and number of homework problems in each set.

| Week numbera | HW nameb | HW numberc | Dued | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Series/Parallel | HW 1 | End of 2nd week | Identify R, L, C, voltage and current sources, nodes, and loops, series and parallel connections. |

| Week 2 | Resistor simplification | HW 2 | End of 2nd week | Simplify a network of resistors using series and parallel transformations. |

| Week 2 | Charge, current, voltage, energy and power | HW 3 | End of 2nd week | Compute charge, currents, voltages, energy and power in single source-load networks. |

| Week 3 | Simple circuits (I) | HW 4 | End of 3rd week | Compute currents, voltages, and powers (dissipated and generated) in circuits with one source and one resistor. |

| Week 3 | Simple circuits (II) | HW 5 | End of 3rd week | Compute currents, voltages, and powers in circuits with 3 or more components, using KVL, KCL, resistor simplifications, current and voltage division. |

| Week 4 | DC nodal analysis (eqs.) | HW 6 | Beginnig of 5th week | Write the system of nodal analysis equations (but do not solve it). |

| Week 4 | DC nodal analysis (num.) | HW 7 | Beginnig of 5th week | Write and solve the system of nodal analysis equations to compute currents, voltages and powers. |

| Week 5 | DC mesh analysis (eqs.) | HW 8 | End of 6th week | Write the system of mesh analysis equations (but do not solve it). |

| Week 5 | DC mesh analysis (num.) | HW 9 | End of 6th week | Write and solve the system of mesh analysis equations to compute currents, voltages and powers. |

| Week 6 | Midterm 1 | |||

| Week 7 | DC superposition | HW 10 | Beginning of 8th week | Use the superposition method to compute currents and voltages in electric networks. |

| Week 7 | DC source transformation | HW 11 | End of 9th week | Simplify a circuit using successive source transformations. |

| Week 8 | DC Norton/Thévenin | HW 12 | End of 9th week | Compute the Norton and Thévenin equivalent circuits or DC networks. |

| Week 9 | DC OpAmps | HW 13 | End of 10th week | Analyze circuits containing one or more operational amplifiers. |

| Week 10 | Inductors and capacitors | HW 14 | End of 11th week | Current, voltage, charge, power and energy in inductors and capacitors; simplify networks of capacitors and inductors using series and parallel transformations. |

| Week 10 | Impedance simplification | HW 15 | End of 11th week | Compute the effective impedance of an AC network of R, L, and C using series and parallel combinations. |

| Week 11 | AC nodal analysis | HW 16 | Beginnig of 13h week | Compute currents and voltages in AC circuits using nodal analysis. |

| Week 12 | AC mesh analysis | HW 17 | Beginnig of 14th week | Compute currents and voltages in AC circuits using mesh analysis. |

| Week 13 | AC analysis | HW 18 | End of 14th week | Use superposition, Norton and Thévenin, and other AC analysis techniques (including time-domain/complex transformations) to solve AC problems. |

| Week 14 | Midterm 2 | |||

| Week 15 | AC OpAmps | HW 19 | End of 15th week | Single OpAmp inverters and followers containing AC sources, resistors, inductors, and capacitors. |

| Week 16 | Final exam | |||

aThe week when the topic is covered in class.

bThe default homework name when a new course is generated in CircuitsU.

cThe default homework number when a new course is generated in CircuitsU.

dThese are only the recommended due date, however, they need to be set by the instructor. Shorter homework assignments can have the same due date.

Semester 2

Below are the default assignments (HW1-HW17) that are generated when the instructor creates a new Linear Circuit Analysis course and choses Semester 2 in a 2-semester course.

| Week number | HW | HW number | Due | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | AC power | HW 1 | Beginning of 3nd week | Compute real power, reactive power, complex power, and power factor in AC circuits; power factor correction methods. |

| Week 2 | AC maximum power transfer | HW 2 | Beginning of 3rd week | Compute maximum power transferred in AC circuits; AC power factor correction. |

| Week 3 | Magnetically coupled inductors | HW 3 | Beginning of 4rd week | Compute currents and voltages in AC networks containing coupled inductors using mesh analysis. |

| Week 3 | Ideal transformers | HW 3 | Beginning of 4rd week | Compute currents and voltages in AC networks containing ideal transformers using nodal or mesh analysis, or the transformer elimination method. |

| Week 4 | Polyphase circuits | HW 5 | Beginning of 5th week | Three-phase circuits, delta-wye transformations, power, and power factor. |

| Week 4 | RLC resonant circuits | HW 6 | End of 5th week | Compute the resonant frequency, the quality factor, the band width, and half-power frequencies in RLC series and parallel circuits. |

| Week 5 | First-order transient circuits | HW 7 | Beginning of 7th week | Use the time relaxation approach to compute currents and voltages in first-order transient circuits. |

| Week 6 | Midterm 1 | |||

| Week 7 | Nodal analysis using ODEs (eqs.) | HW 8 | Beginning of 9th week | Write the system of nodal analysis ODEs for first, second and higher-order transient circuits (zero and non-zero initial conditions). |

| Week 8 | Mesh analysis using ODEs (eqs.) | HW 9 | Beginning of 9th week | Write the system of mesh analysis ODEs for first, second and higher-order transient circuits (zero and non-zero initial conditions). |

| Week 9 | Laplace transforms | HW 10 | End of 10th week | Compute the direct Laplace transform of various functions. |

| Week 9 | Inverse Laplace transforms | HW 11 | End of 10th week | Compute the inverse Laplace transform of various functions. |

| Week 10 | Laplace impedance simplification | HW 12 | End of 11th week | Transform a circuit to s-domain and compute its equivalent s-domain impedance. |

| Week 10 | Nodal analysis in s-domain (num.) | HW 13 | End of 12th week | Convert circuits to s-domain, then write and solve the system of nodal analysis equations for first and second-order transient circuits (zero initial conditions). |

| Week 11 | Mesh analysis in s-domain (num.) | HW 14 | End of 12th week | Convert circuits to s-domain, then write and solve the system of mesh analysis equations for first and second-order transient circuits (zero initial conditions). |

| Week 12 | Source transformation in s-domain (num.) | HW 15 | Beginning of 13th week | Source transformations, Norton/Thévenin equivalent circuits and superposition in the s-domain (zero initial conditions). |

| Week 13 | Bode plots | HW 16 | Beginning of 14th week | Derive the transfer function from the Bode magnitude plot and draw the Bode magnitude plot of a transfer function. |

| Week 14 | Midterm 2 | |||

| Week 15 | Two-port networks | HW 17 | End of 15th week | Compute y, z, h, and t parameters of DC and AC two-port networks. |

| Week 16 | Final exam | |||

1.5 3-Quarter Courseplan

Quarter 1

Below are the default assignments (HW1-HW12) that are generated when the instructor creates a new Linear Circuit Analysis course and choses Quarter 1 in a 3-quarter course. The table shows the proposed due dates for each HW set but each instructor can set his or her own time schedule. The instructor can also re-organize the content and change the type, difficulty, and number of homework problems in each set.

| Week numbera | HW nameb | HW numberc | Dued | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Series/Parallel | HW 1 | End of 2nd week | Identify R, L, C, voltage and current sources, nodes, and loops, series and parallel connections. | |

| Week 2 | Resistor simplification | HW 2 | End of 2nd week | Simplify a network of resistors using series and parallel transformations. | |

| Week 3 | Simple circuits (I) | HW 3 | End of 3rd week | Compute currents, voltages, and powers (dissipated and generated) in circuits with one source and one resistor. | |

| Week 3 | Simple circuits (II) | HW 4 | End of 3rd week | Compute currents, voltages, and powers in circuits with 3 or more components, using KVL, KCL, resistor simplifications, current and voltage division. | |

| Week 4 | DC nodal analysis (eqs.) | HW 5 | End of 4th week | Write the system of nodal analysis equations (but do not solve it). | |

| Week 4 | DC nodal analysis (num.) | HW 6 | End of 4th week | Write and solve the system of nodal analysis equations to compute currents, voltages and powers. | |

| Week 5 | DC mesh analysis (eqs.) | HW 7 | Beginning of 6th week | Write the system of mesh analysis equations (but do not solve it). | |

| Week 5 | DC mesh analysis (num.) | HW 8 | Beginning of 6th week | Write and solve the system of mesh analysis equations to compute currents, voltages and powers. | |

| Week 6 | Review session or optional midterm | ||||

| Week 7 | DC superposition | HW 9 | Beginning of 8th week | Use the superposition method to compute currents and voltages in DC networks. | |

| Week 7 | DC source transformation | HW 10 | Beginning of 9th week | Simplify a circuit using successive source transformations. | |

| Week 8 | DC Norton/Thévenin | HW 11 | Begining of 9th week | Compute the Norton and Thévenin equivalent circuits or DC networks. | |

| Week 9 | DC OpAmps | HW 12 | Beginning of 10th week | Analyze circuits containing one or more operational amplifiers. | |

| Week 10 | Final exam | ||||

aThe week when the topic is covered in class.

bThe default homework name when a new course is generated in CircuitsU.

cThe default homework number when a new course is generated in CircuitsU.

dThese are only the recommended due date, however, they need to be set by the instructor. Shorter homework assignments can have the same due date.

Quarter 2

Below are the default assignments (HW1-HW14) that are generated when the instructor creates a new Linear Circuit Analysis course and choses Quarter 2 in a 3-quarter course.

| Week number | HW name | HW number | Due | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Inductors and capacitors | HW 1 | End of 2nd week | Current, voltage, charge, power and energy in inductors and capacitors; simplify networks of capacitors and inductors using series and parallel transformations. | |

| Week 2 | Impedance simplification | HW 2 | End of 2nd week | Compute the effective impedance of an AC network of R, L, and C using series and parallel combinations. | |

| Week 3 | AC nodal analysis | HW 3 | Beginnig of 4th week | Write the system of nodal analysis equations (but do not solve it). | |

| Week 3 | AC nodal analysis | HW 4 | Beginnig of 4th week | Write and solve the system of nodal analysis equations compute currents and voltages. | |

| Week 4 | AC mesh analysis | HW 5 | End of 5th week | Write the system of mesh analysis equations (but do not solve it). | |

| Week 4 | AC mesh analysis | HW 6 | End of 5th week | Write and solve the system of mesh analysis equations to compute currents and voltages. | |

| Week 5 | AC superposition | HW 7 | End of 6th week | Use the superposition method to compute currents and voltages in DC networks | |

| Week 5 | AC Norton/Thévenin | HW 8 | Beginning of 7th week | Compute the Norton and Thévenin equivalent circuits or AC networks. | |

| Week 6 | Review session or optional midterm | ||||

| Week 7 | AC analysis | HW 9 | Beginning of 8th week | Use a.c techniques to solve general AC circuits. | |

| Week 7 | AC OpAmps | HW 10 | Beginning of 8th week | Single OpAmp inverters and followers containing AC sources, resistors, inductors, and capacitors. | |

| Week 8 | AC power | HW 11 | Beginning of 9nd week | Compute real power, reactive power, complex power, and power factor in AC circuits; power factor correction methods. | |

| Week 8 | AC maximum power transfer | HW 12 | Beginning of 9th week | Compute maximum power transferred in AC circuits; AC power factor correction. | |

| Week 9 | AC coupled inductors | HW 13 | End of 9th week | Compute currents and voltages in AC networks containing coupled inductors using mesh analysis. | |

| Week 9 | AC ideal transformers | HW 14 | End of 9th week | Compute currents and voltages in AC networks containing ideal transformers using nodal or mesh analysis, or the transformer elimination method. | |

Quarter 3

Below are the default assignments (HW1-HW13) that are generated when the instructor creates a new Linear Circuit Analysis course and choses Quarter 3 in a 3-quarter course.

| Week number | HW name | HW number | Due | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Polyphase circuits | HW 1 | End of 2nd week | Three-phase circuits, delta-wye transformations, power, and power factor. | |

| Week 1 | RLC resonant circuits | HW 2 | End of 2rd week | Compute the resonant frequency, the quality factor, the band width, and half-power frequencies in RLC series and parallel circuits. | |

| Week 2 | First-order transient circuits | HW 3 | End of 3th week | Use the time relaxation approach to compute currents and voltages in first-order transient circuits. | |

| Week 3 | Nodal analysis using ODEs (eqs.) | HW 4 | Beginning of 4th week | Write the system of nodal analysis ODEs for first, second and higher-order transient circuits (zero and non-zero initial conditions). | |

| Week 4 | Mesh analysis using ODEs (eqs.) | HW 5 | Beginning of 4th week | Write the system of mesh analysis ODEs for first, second and higher-order transient circuits (zero and non-zero initial conditions). | |

| Week 5 | Laplace transforms | HW 6 | Beginning of 6th week | Compute the direct Laplace transform of various functions. | |

| Week 5 | Inverse Laplace transforms | HW 7 | Beginning of 6th week | Compute the inverse Laplace transform of various functions. | |

| Week 6 | Review session or optional midterm | ||||

| Week 7 | Laplace impedance simplification | HW 8 | Beginning of 7th week | Transform a circuit to s-domain and compute its equivalent s-domain impedance. | |

| Week 7 | Nodal analysis in s-domain (num.) | HW 9 | End of 7th week | Convert circuits to s-domain, then write and solve the system of nodal analysis equations for first and second-order transient circuits (zero initial conditions). | |

| Week 8 | Mesh analysis in s-domain (num.) | HW 10 | End of 8th week | Convert circuits to s-domain, then write and solve the system of mesh analysis equations for first and second-order transient circuits (zero initial conditions). | |

| Week 8 | Source transformation in s-domain (num.) | HW 11 | Beginning of 9th week | Source transformations, Norton/Thévenin equivalent circuits and superposition in the s-domain (zero initial conditions). | |

| Week 9 | Bode plots | HW 12 | Beginning of 10th week | Derive the transfer function from the Bode magnitude plot and draw the Bode magnitude plot of a transfer function. | |

| Week 9 | Two-port networks | HW 13 | Beginning of 10th week | Compute y, z, h, and t parameters of DC and AC two-port networks. | |

| Week 10 | Final exam | ||||

1.6 Notations

This webbook and CircuitsU use the following notations:

| $I$, $V$, $P_d$, and $P_g$ | DC currents, voltages, and powers are denoted with capital letters |

| $I$, $V$, $P_d$, and $P_g$ | currents, voltages, and powers in the frequency (complex) and s-domains are denoted with capital letter* |

| $I(t)$, $V(t)$, $P_d(t)$, and $P_g(t)$ | time-dependent currents, voltages, and powers are usually shown as functions of time |

| $I(t)=I_0 \cos(\omega t+\phi)$ $V(t)=V_0\sin(\omega t+\phi)$ | AC currents AC voltages |

| $v_1$, $v_2$,... | nodal potentials (real, complex, or in the s-domain) are written in lowercases |

| $i_1$, $i_2$,... | mesh currents (real, complex, or in the s-domain) are written in lowercases |

| $v_1(t)$, $v_2(t)$,... | nodal potentials in time-domain |

| $i_1(t)$, $i_2(t)$,... | mesh currents in time-domain |

| $\class{mjblue}{j}$ | imaginary number $j=\sqrt{-1}$ |

| $\class{mjblue}{s}$ | complex frequency used in Laplace transforms |

| $\omega$ | angular frequency |

*A better notation, which is often used in textbooks, is to use bold letters for complex variables ($\boldsymbol{I}$, $\boldsymbol{V}$, $\boldsymbol{P_d}$, and $\boldsymbol{P_g}$) however, due to limitations in SVG graphic fonts the website uses regular fonts for both real and complex variables.

Subscripts

| $0$ | denotes sought variables (e.g. $V_0$, $I_0$) |

| $eff$ | effective (e.g. $R_{eff}$, $L_{eff}$,...) |

| $rms$ | root-mean square (e.g. $V_{rms}$, $I_{rms}$) |

| $d$ | dissipated (e.g. $P_d$) |

| $g$ | generated (e.g. $P_g$) |

| $N$ | Norton |

| $Th$ | Thévenin |

| $1$, $2$, ... | used for mesh currents (e.g. $i_1$, $i_2$,...), nodal potentials (e.g. $v_1$, $v_2$,...), components (e.g. $R_1$, $L_1$, $C_1$, $V_1$, $I_1$,...) |

| $x$, $y$, ... | used for control variables (e.g. $I_x$, $V_y$,...) |

Abbreviations

| AC | alternating current |

| DC | direct current (continuous current) |

| KCL | Kirchhoff's current law |

| KVL | Kirchhoff's voltage law |

| OpAmp | operational amplifier |

| TD | time-dependent |

Units

All variables are assumed to be expressed in the International System of Units in CircuitsU. Therefore, to simplify notations, CircuitsU will usually not write the units in mathematical expressions unless it is a final answer.

Units are written with gray characters in CircuitsU. For instance: $V_1 = 2.4 \: {\class{mjunit}{V}}$, $R = \frac{2.4 \: {\class{mjunit}{V}}}{1.2 \: {\class{mjunit}{A}}} =2 \: {\class{mjunit}{Ω}}$.

2. Basic Concepts

2.1 Electric Charge ($Q$)

Electric charge is a concept rigorously defined in electrostatics in terms of the properties matter exhibits when placed in an electromagnetic field. In the context of electric circuits, we are interested in the charge flowing through wires (or entering or leaving the terminal of a component). This charge equals the number of electrons passing through the wire ($N$) multiplied by the charge of a single electron ($-q$), where $q$ is the elementary charge: $$\begin{equation}q=1.602\times10^{-19}\:{\class{mjunit}C}\end{equation}$$

The SI unit of charge is the coulomb (${\class{mjunit}C}$). The name comes from the French physicist Charles-Augustin de Coulomb (1736–1806), who is best known for formulating Coulomb’s law, which describes the electrostatic force between two point charges $Q_1$ and $Q_2$: $$\begin{equation}F=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{Q_1 Q_2}{r^2}\end{equation}$$ where $\epsilon_0$ is the electric permittivity of vacuum and $r$ is the distance between the two charges.

2.2 Electric Current ($I$)

The electric current going through a wire is defined as the charge that goes through that wire in unit time $$\begin{equation}I(t)=\frac{dQ}{dt}\end{equation}$$ The SI unit of electric current is the ampere or amp (${\class{mjunit}A}$). The conventional symbol for current is $I$ (see Fig. 2.1), which originates from the French phrase intensité du courant, (current intensity). The $I$ symbol was first used by André-Marie Ampère (1775–1836), after whom the unit of electric current is named.

The current can flow in either of the two directions in a wire. When defining a variable $I$ to represent the current, the direction representing positive current must be specified, usually by an arrow on the wire. This is the reference direction of the current. The actual direction of current through a specific circuit element is usually unknown until the current is computed numerically or measured experimentally. Consequently, the reference directions of the currents are often assigned arbitrarily when we start analyzing a circuit. After the circuit is solved, a negative value for the current implies that the actual direction of the current is opposite than that of the reference direction.

If the current is known, one can compute the total charge that goes through the wire from time $t=0$ to $T$ by integrating the previous equation $$\begin{equation}Q(T)=\int_{0}^T I(t) dt\end{equation}$$

2.3 Electric Potential and Voltage ($V$)

The electric potential, also known as electrostatic potential (or simply potential), is defined as the amount of work required to move a unit charge from a reference point (often taken at infinity) to a specified point. In electric circuit analysis, the reference point is conventionally chosen as the ground node, whose potential is assumed to be zero. The SI unit of electric potential is the volt (${\class{mjunit}V}$). The name comes from the Italian physicist Alessandro Volta (1745–1827), who invented the first chemical battery, known as the Voltaic pile.

Ideal wires are defined as wires with zero internal resistance. Therefore, the amount of work to move electrons from one point of an wire to another point of the same wire is equal to $0$. In addition, the electric potential of an ideal wire is the same at any point on the wire.

Voltage, also known as (electric) potential difference, is the difference of the electric potential between two points. Therefore, the SI unit of the voltage is the same as for electric potential, the volt. If we denote the two points by $A$ and $B$ and the potentials at those two points by $V_A$ and $V_B$, the voltage between the two points is $$\begin{equation}V_{AB}=V_{A}-V_{B}\end{equation}$$ To simplify the notations on circuit diagrams, we often denote point $A$ (the first point) with $+$ and point $B$ (the second point) with $-$ (see Fig. 2.1). In this case, voltage $V$ is understood to be the voltage from the node denoted with $+$ to the node denoted with $-$.

Finally, using the previous equation it is obvious that $$\begin{equation}V_{AB}=-V_{BA}\end{equation}$$

-

Analytical

Compute current when charge is given analytically

Compute charge when current is given analytically

Compute charge or current entering a box analytically

-

Graphical

Compute current when charge is given graphically (2 intervals)

Compute current when charge is given graphically (3 intervals)

Compute current when charge is given graphically (4 intervals)

Compute current when charge is given graphically (5 intervals)

Compute current when charge is given graphically (6 intervals)

Compute current when charge is given graphically (7 intervals)

Compute charge when current is given graphically (2 intervals)

Compute charge when current is given graphically (3 intervals)

Compute charge when current is given graphically (4 intervals)

Compute charge when current is given graphically (5 intervals)

Compute charge when current is given graphically (6 intervals)

Compute charge when current is given graphically (7 intervals)

Compute charge or current entering a box graphically (2 intervals)

Compute charge or current entering a box graphically (3 intervals)

Compute charge or current entering a box graphically (4 intervals)

Compute charge or current entering a box graphically (5 intervals)

Compute charge or current entering a box graphically (6 intervals)

Compute charge or current entering a box graphically (7 intervals)

2.4 Linear Circuits

Linear circuits are circuits that contain only linear components such as resistors, capacitors, inductors, ideal voltage and current sources, transformers, operational amplifiers, etc. Table 2.1 from the Linear components section presents a list of linear components together with their current-voltage characteristics. The current-voltage characteristics completely define the component for an electrical standpoint and, once these characteristics are known, one can completely predict how the component behaves in an electric circuit. In this course, we are focusing only on ideal components that do not break at higher voltages (in which case they would be considered non-linear).

Linear components of linear devices are those devices that have linear current-voltage characteristics. Intuitively, the current-voltage characteristic of a device is linear if it can be represented graphically by straight line on a current-voltage $V(I)$ or voltage-current $I(V)$ plot. Mathematically, a component is linear if for any currents $I_1$ and $I_2$ going through the device the voltage across the device satisfies $$\begin{equation} V(aI_1+bI_2)=aV(I_1)+bV(I_2) \end{equation}$$ or for any voltages $V_1$ and $V_2$ across the device the current going through the device satisfies $$\begin{equation} I(aV_1+bV_2)=aI(V_1)+bI(V_2) \end{equation}$$ where $a$ and $b$ are any real constants. It turns out that the analysis of linear circuits requires solving linear systems of equations, which can be algebraic equations with real or complex coefficients or linear ordinary differential equations.

Nonlinear circuits are circuits that contain at least one nonlinear component, which is a component in which the current-voltage characteristic is nonlinear. Examples of nonlinear components are diodes, transistors, and nonlinear sensors or actuators. Most often, real (practical) linear components such as voltage and current sources, resistors, transformers, etc. can be treated as linear on a small range of applied voltages and currents and they can become nonlinear if we increase this range. Nonlinear circuits can also be analyzed unsing Kirchhoff's laws, however, they will lead to systems of nonlinear equations that are usually more difficult to solve than systems of linear equations.

Importance

Linear circuits are also relatively easy to understand and study mathematically. Since they are linear, these circuits can be described by linear algebraic or differential equations, which can be always solved using simple algebra or linear differential equations theory. Unlike linear circuits, nonlinear circuits are described by nonlinear equations, which are usually more difficult to solve mathematically.

In practical applications, linear circuits are important because they do not distort the shape of the input signal. For this reason they can be used as amplifiers, voltage or current attenuators, linear sensors, etc.

Linear Components (Devices)

Table 2.1 shows a list of linear components (also called devices or elements) used in linear circuit analysis. All the components (and, implicitly, their current-voltage characteristics) are assumed to be ideal.

| Name/Unit | Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Resistor Ohms, $Ω$ |

Resistors

|

A resistor is a 2-terminal device that satisfies Ohm's law:$$\begin{equation}V(t)=I(t)R\end{equation}$$ where $R$ is the resistance and $V(t)$ is the voltage from the terminal where current $I(t)$ is assumed to enter the resistor to the terminal where the current is assumed to exit the resistor. In the case of DC circuits (i.e. when the voltage and current do not depend on time) the above equation is usually written as $V=IR$, where $V$ and $I$ are the DC values of the voltage and current. In the case of AC circuits (in frequency domain) the Ohm's law can be written in the same way, but $V$ and $I$ are the complex values of the voltage and current.

Why do resistors warm up? When current flows through a resistor, the moving charge carriers (usually electrons) collide with the atoms of the resistive material. These collisions impede the flow of electrons and convert part of the electrical energy into random thermal motion of the atoms — i.e., heat and possibly into light. This process in which the electrical energy is converted into heat is called Joule heating (or resistive heating). |

|

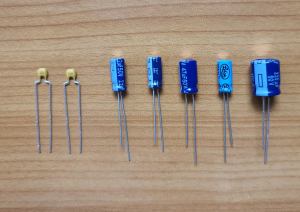

Capacitor Faradays, $F$ |

Ceramic and electrolytic capacitors

|

A capacitor is a 2-terminal device in which the current and voltage satisfy the following equation $$\begin{equation}I(t)=C\dfrac{dV(t)}{dt}\end{equation}$$ where $C$ is the capacitance (see figure for notations). Can the voltage across a capacitor change instantaneously? The answer is no, because doing so would cause the voltage across the inductor to become infinite (see the equation above). As a result, the current through an inductor cannot change instantaneously. In practice, one should always avoid sudden changes in the current through an inductor—for example, abruptly disconnecting the inductor from the circuit. In such a case, forcing the current to drop instantaneously from its initial value to zero can produce a very large voltage spike, potentially damaging the inductor or other circuit components. Instead, the energy stored in the inductor’s magnetic field will try to keep the current flowing, often discharging through a spark, arc, or protection device if no other path is provided. Capacitors can be divided into polarized and non-polarized types:

|

|

Inductor Henries, $H$ |

Inductors

|

An inductor is a 2-terminal device in which the current and voltage satisfy the following equation $$\begin{equation}V(t)=L\dfrac{dI(t)}{dt}\end{equation}$$ where $L$ is the inductance (see figure for notations). Can the current through an inductor change instantaneously? The answer is no, because doing so the voltage across the inductor would become infinite (see the equation above). As a result, the current through an inductor cannot change instantaneously. In practice, one should always avoid sudden changes in the current through an inductor—for example, suddently disconnecting the inductor from the circuit. In such a case, the current would decrease instantaneously from the initial value to 0, which could damage the inductor.. Can the current through an inductor change instantaneously? The answer is no, because doing so the voltage across the inductor would become infinite (see the equation above). As a result, the current through an inductor cannot change instantaneously. In practice, one should always avoid sudden changes in the current through an inductor—for example, suddently disconnecting the inductor from the circuit. In such a case, the current would decrease instantaneously from the initial value to 0, which could damage the inductor.. |

| Impedance Ohms, $Ω$ |

An impedance is a 2-terminal device that is defined in the frequency domain (i.e. in AC circuits) and in which the complex current and complex voltage satisfy the following equation $$\begin{equation}V=Z I\end{equation}$$ where $Z$ is the (complex) impedance (see figure for notations). Notice that the same symbol (rectangle) is sometimes used to represent a "black" box, which is an electronic component with two terminals that can contain a combinations of resistors, inductors, capacitors, sources, etc. | |

|

Voltage source (independent) Volts, $V$ |

An independent voltage source is a 2-terminal device in which the voltage from the positive to the negative terminals is always equal to $V$. The current flowing through a voltage source is generally unknown until the circuit is solved analytically (or the current is measured experimentally). If a voltage source is short-circuited, the circuit presents almost zero resistance to the source. As a result, the current rises dramatically, often far exceeding the source’s rated output. In general, this should never be done, as the excessive current can damage the source unless it is equipped with an appropriate protection mechanism. |

|

|

Current source (independent) Amperes, $A$ |

An independent current source is a 2-terminal device in which the current flowing in the direction of the arrow is always equal to $I$. The voltage accross a current source is generally unknown until the circuit is solved analytically (or the voltage is measured experimentally). Note that a current source adjusts the voltage across its terminals to maintain the current at its specified value. But what happens if a current source is disconnected from the circuit so that its terminals are left open? In practice, one should never do this, because with no path for current flow the source may develop an excessively high voltage and could be damaged unless it is equipped with a protection mechanism. |

|

| Dependent voltage source Volts, $V$ |

A dependent voltage source is a 2-terminal device in which the voltage from the positive to the negative terminals is equal to the value indicated ($V_x$ in this case), which can depend on other currents and voltages in circuit. | |

| Dependent current source Amperes, $A$ |

A dependent current source is a 2-terminal device in which the current flowing in the direction of the arrow is equal to the value indicated ($I_x$ in this case), which can depend on other currents and voltages in circuit. |

In addition to the linear components listed in Table 2.1, other examples of linear devices include transformers, operational amplifiers, and linear sensors. The first two of these components—transformers and operational amplifiers—will be studied in detail in later sections of this WebBook.

-

Identify resistors, capacitors, inductors, current and voltage sources in electric networks

Circuit with resistors, capacitors, inductors and independent sources

Circuit with resistors, capacitors, inductors, dependent and independent sources

2.5 Loops (meshes)

A loop (or mesh) is any closed path through the circuit in which nodes appear at most once. Meshes are defined in planar circuits, which are circuits that can be drawn on a plane surface with no wires crossing each other. Loops are slightly more general and can be applied to any circuit, planar or not. Since all the electric circuits that appear on this website are planar, we will use mesh and loop interchangeably.

A minor mesh (or minor loop) is a mesh that does not contain any other meshes. The outer mesh (or outer loop) of a circuit includes all the minor meshes in the circuit and is usually considered as a reference mesh.

A circuit can have multiple loops (or meshes). For instance, the circuit shown in Fig. 2.4 has 3 minor meshes labeled $i_1$, $i_2$, and $i_3$ and the outer mesh. Since, we are almost always interested only in the minor meshes and the outer mesh, we will simply say that that the circuit below contains 3 meshes (or 3 loops) plus the outer mesh (or outer loop).

Loops and meshes are made of branches.

Any circuit should contain at least one mesh. When the circuit contains only one mesh (which is the same as the outer mesh), it is called single loop circuit (see Fig. 2.5).

Mesh analysis is a method based on Kirchhoff's voltage law that can be used to analyze planar electric circuits. Loop analysis is slightly more general and can be applied to non-planar circuits. Mesh analysis is usually easier to use than loop analysis because the circuit is planar. However, notice again that, since all the electric circuits on this website are planar, we will use the names mesh analysis and loop analysis interchangeably.

-

Identify loops in electric networks

Circuit with 2 loops with resistors and a voltage source

Circuit with 4 loops with resistors, a voltage source and a current source

Circuit with 4-6 loops with resistors and dependent and independent sources

Circuit with 7-9 loops with resistors and dependent and independent sources

2.6 Nodes

A node is a collection of wires that are connected to each other. A circuit can have multiple nodes. For instance, the circuit shown in Fig. 2.6 has 5 nodes labeled $v_1$, $v_2$, $v_3$, $v_4$, and $v_5$.

Sometimes, one of the nodes is called the ground node. For instance, the circuits shown in Fig. 2.7 and Fig. 2.8 contain 4 nodes labeled $v_1$, $v_2$, $v_3$, and $v_4$, and the ground node (5 nodes in total). Notice that the two circuits have the same topology and the currents going through and the voltages across each component are the same.

Any circuit should contain at least 2 nodes (see Fig. 2.9). When the circuit contains only 2 nodes, it is called a single node-pair circuit.

Nodal analysis is a method based on Kirchhoff's current law that can be used to analyze electric circuits.

-

Identify nodes in electric networks

Circuit with 2 loops with resistors and a voltage source

Circuit with 4 loops with resistors, a voltage source and a current source

Circuit with 4-6 loops with resistors and dependent and independent sources

Circuit with 7-9 loops with resistors and dependent and independent sources

2.7 Series Connections

Two or more components (each with two terminals) are connected in series when they are part of the same two minor meshes, or, to one minor mesh and the outer mesh. For instance, in Fig. 2.10:

- Voltage source $V_1$ and resistor $R_1$ are connected in series because they both belong to minor mesh $i_1$ and the outer mesh.

- Current source $I_1$ and capacitor $C_1$ are connected in series because they both belong to minor mesh $i_3$ and the outer mesh.

- However, resistor $R_3$ and inductor $L_1$ are not connected in series because they belong to different pair of minor meshes (resistor $R_3$ belongs to $i_1$ and $i_2$, while inductor $L_1$ belongs to the outer mesh and $i_2$.

In Fig. 2.11:

- Voltage source $V_1$ and inductor $L_1$ are connected in series because they both belong to minor mesh $i_2$ and the outer mesh.

- Capacitor $C_1$, current source $I_1$ and capacitor $C_2$ are connected in series because they all belong to minor mesh $i_3$ and the outer mesh.

- Resistor $R_2$ and inductor $L_2$ are connected in series because they both belong to minor meshes $i_2$ and $i_3$.

If one component is connected in series with a second component, and the second component is connected in series with the third component, then the first component is also connected in series with the third component.

Parallel Connections

Two or more components (each having two terminals) are connected in parallel when they are connected between the same two nodes. For instance, looking at the circuit in Fig. 2.11:

- Capacitor $C_3$ and resistor $R_1$ are connected in parallel because they are both connected between nodes $v_2$ and $v_3$.

- However, inductors $L_1$ and $L_2$ are not connected in parallel because they are not connected between the same two nodes (inductor $L_1$ is connected between $v_3$ and $v_6$, while inductor $L_2$ is connected between $v_4$ and $v_6$).

If one component is connected in parallel with a second component, and the second component is connected in parallel with the third component, then the first component is also connected in parallel with the third component.

-

Identify series and parallel connections in electric networks

Circuit with 2 loops with resistors and a voltage source

Circuit with 4 loops with resistors, a voltage source and a current source

Circuit with 4-6 loops with resistors and dependent and independent sources

Circuit with 7-9 loops with resistors and dependent and independent sources

2.8 Resistor Combinations

Series

If two or more resistors $R_1$, $R_2$, ... $R_n$ are connected in series they are equivalent to a single resistor a resistor with $$\begin{equation}R_{eff}=R_1+R_2+...+R_n\end{equation}$$ That means we can replace one of the $n$ resistors with an equivalent resistor with resistance $R_{eff}$ and replace the other resistors with short-circuits (wires).

For instance, in Fig. 2.12, resistors $R_1$ and $R_2$ are connected in series. Therefore, we can keep one of the resistors, say $R_1$, replace its value with $R_{eff}=R_1+R_2$, and replace resistor $R_2$ with a wire.

Parallel

If two or more resistors $R_1$, $R_2$, ... $R_n$ are connected in parallel they are equivalent to a single resistor a resistor with $$\begin{equation}R_{eff}=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{R_1}+\frac{1}{R_2}+...+\frac{1}{R_n}}\end{equation}$$ That means we can replace one of the $n$ resistors with an equivalent resistor with resistance $R_{eff}$ and remove all the other resistors. When we have only two resistors connected in parallel, we can replace them with a single resistor with resistance $$R_{eff}=\frac{R_1 R_2}{R_1+R_2}$$

For instance, in Fig. 2.13, resistors $R_3$, $R_4$, and $R_5$ are connected in parallel. Therefore, we can keep one of the resistors, say $R_3$, replace its value with $R_{eff}=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{R_3}+\frac{1}{R_4}+\frac{1}{R_5}}$, and remove resistor $R_4$ from the circuit. Similarly, we could keep $R_4$ and remove $R_3$ and $R_5$, or keep $R_5$ and remove $R_3$ and $R_4$.

2.9 Inductor Combinations

Series

If two or more inductors $L_1$, $L_2$, ... $L_n$ are connected in series they are equivalent with a inductor with $$\begin{equation}L_{eff}=L_1+L_2+...+L_n\end{equation}$$ That means we can replace one of the $n$ inductors with an equivalent inductor with inductance $L_{eff}$ and replace the other inductors with short-circuits (wires).

For instance, consider the circuit in Fig. 2.14, in which inductors $L_1$ and $L_2$ are connected in series. In this circuit, we can keep one inductor, say $L_1$, replace its value with $L_{eff}=L_1+L_2$, and replace inductor $L_2$ with a wire.

Parallel

If two or more inductors $L_1$, $L_2$, ... $L_n$ are connected in parallel they are equivalent with a inductor with $$\begin{equation}L_{eff}=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{L_1}+\frac{1}{L_2}+...+\frac{1}{L_n}}\end{equation}$$ That means we can replace one of the $n$ inductors with an equivalent inductor with inductance $L_{eff}$ and remove all the other inductors. When we have only two inductors connected in parallel, we can replace them with a single inductors with inductance $$L_{eff}=\frac{L_1 L_2}{L_1+L_2}$$

For instance, consider the circuit in Fig. 2.15, in which inductors $L_3$, $L_4$, and $L_5$ are connected in parallel. In this circuit, we can keep one inductor, say $L_3$, replace its value with $L_{eff}=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{L_3}+\frac{1}{L_4}+\frac{1}{L_5}}$, and remove inductor $L_4$ from the circuit. Similarly, we could keep $L_4$ and remove $L_3$ and $L_5$, or keep $L_5$ and remove $L_3$ and $L_4$.

2.10 Capacitor Combinations

Series

If two or more capacitors $C_1$, $C_2$, ... $C_n$ are connected in series they are equivalent with a capacitor with $$\begin{equation}C_{eff}=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{C_1}+\frac{1}{C_2}+...+\frac{1}{C_n}}\end{equation}$$ That means we can replace one of the $n$ capacitors with an equivalent capacitor with capacitance $C_{eff}$ and replace the other capacitors with short-circuits (wires). When we have only two capacitors connected in parallel, we can replace them with a single capacitors with capacitance $$C_{eff}=\frac{C_1 C_2}{C_1+C_2}$$

For instance, consider the circuit in Fig. 2.16, in which capacitors $C_1$ and $C_2$ are connected in series. In this circuit, we can keep one capacitor, say $C_1$, replace its value with $C_{eff}=\frac{C_1 C_2}{C_1+C_2}$, and replace capacitor $C_2$ with a wire.

Parallel

If two or more capacitors $C_1$, $C_2$, ... $C_n$ are connected in parallel they are equivalent with a capacitor with $$\begin{equation}C_{eff}=C_1+C_2+...+C_n\end{equation}$$ That means we can replace one of the $n$ capacitors with an equivalent capacitor with capacitance $C_{eff}$ and remove all the other capacitors.

For instance, consider the circuit in Fig. 2.17, in which capacitors $C_3$, $C_4$, and $C_5$ are connected in parallel. In this circuit, we can keep one of the capacitors, say $C_3$, replace its value with $C_{eff}=C_3+C_4+C_5$, and remove capacitors $C_4$ and $C_5$ from the circuit. Similarly, we could keep $C_4$ and remove $C_3$ and $C_5$, or keep $C_5$ and remove $C_3$ and $C_4$.

-

Resistance simplifications (analytical)

Circuit with 2 loops, 4-6 resistors (analytical)

Circuit with 3 loops, 6 resistors (analytical)

Circuit with 5 loops, 8 resistors (analytical)

-

Resistance simplifications (numerical)

Circuit with 2 loops, 4-6 resistors (numerical)

Circuit with 3 loops, 6 resistors (numerical)

Circuit with 5 loops, 8 resistors (numerical)

Circuit with 8 loops, 13 resistors (numerical)

-

Inductance simplifications (analytical)

Circuit with 2 loops, 4-6 inductors (analytical)

Circuit with 3 loops, 6 inductors (analytical)

Circuit with 5 loops, 8 inductors (analytical)

-

Inductance simplifications (numerical)

Circuit with 2 loops, 4-6 inductors (numerical)

Circuit with 3 loops, 6 inductors (numerical)

Circuit with 5 loops, 8 inductors (numerical)

Circuit with 8 loops, 13 inductors (numerical)

-

Capacitance simplifications (analytical)

Circuit with 2 loops, 4-6 capacitors (analytical)

Circuit with 3 loops, 6 capacitors (analytical)

Circuit with 5 loops, 8 capacitors (analytical)

-

Capacitance simplifications (numerical)

Circuit with 2 loops, 4-6 resistor (numerical)

Circuit with 3 loops, 6 resistor (numerical)

Circuit with 6 loops, 8 resistor (numerical)

Circuit with 8 loops, 13 resistor (numerical)

2.11 Voltage Source Combinations

Series

If two or more voltage sources $V_1$, $V_2$, ... $V_n$ are connected in series they can be replaced with a single voltage source with $$V_{eff}=\pm V_1 \pm V_2\pm...\pm V_n$$ where the terms in the right-hand side are taken with $+$ sign if the corresponding voltage source $V_i$ is oriented in the same direction with $V_{eff}$ and with $-$ sign if $V_i$ is oriented in opposite direction with $V_{eff}$. Since the voltage sources are all connected in series, when we replace $V_i$ with $V_{eff}$, the other voltage sources are replaced with short-circuits (i.e. wires).

For instance, consider the circuit in Fig. 2.18, in which voltage sources $V_1$ and $V_2$ are connected in series (because they belong to both the outer loop and loop $i_1$). In this circuit, we can keep one voltage source, say $V_1$, replace its value with $$\begin{equation}V_{1,eff}=V_1-V_2\end{equation}$$ and replace voltage source $V_2$ with a wire. Notice that $V_1$ appears with a positive sign in the equation above because $V_1$ and $V_{1,eff}$ have the same polarity (i.e., orientation) relative to the reference loop $i_1$. In contrast, $V_2$ appears with a negative sign because $V_2$ and $V_{1,eff}$ have opposite polarities relative to the same reference loop $i_1$.

If we kept the other voltage source, $V_2$, we had to replace its value with $$\begin{equation}V_{2,eff}=V_2-V_1\end{equation}$$ (see figure below). In this case, $V_2$ was taken with positive sign because $V_2$ and $V_{2,eff}$ have the same polarity relative to the reference loop $i_1$, while $V_1$ as taken with a negative sign because its polarity is oposite to the polarity of $V_{1,eff}$ relative to the same reference loop $i_1$.

Parallel

Voltage sources should never be combined in parallel. What would happen if two voltage sources with different voltages are connected in parallel?

2.12 Current Source Combinations

Series

Current sources should never be combined in series. What would happen if we connect two current sources with different currents in series?

Parallel

If two or more current sources $I_1$, $I_2$, ... $I_n$ are connected in parallel they can be replaced with a single current source with $$I_{eff}=\pm I_1 \pm I_2\pm...\pm I_n$$ where the terms in the right-hand side are taken with $+$ sign if the corresponding current source $I_i$ points towards the same node as $I_{eff}$ and with $-$ sign if $I_i$ points to the other node. Since all the current sources are connected in parallel, when we replace $I_i$ with $I_{eff}$, the other current sources are removed (i.e. replaced with open circuits).

For instance, consider the circuit in Fig. 2.19, in which current sources $I_1$, $I_2$, and $I_3$ are connected in parallel. In this circuit, we can keep one current source, say $I_1$, replace its value with $$\begin{equation}I_{1,eff}=I_1-I_2+I_3\end{equation}$$ and remove current sources $I_2$ and $I_3$ from the circuit. Notice that $I_1$ and $I_3$ appear with positive sign in the above equation because both $I_1$ and $I_3$ point towards node $v_3$, just like $I_{1,eff}$. $I_2$ appears with negative sign because it points towards node $v_4$ while $I_{1,eff}$ points towards node $v_3$. If we kept current source $I_2$, we had to replace its value with $$\begin{equation}I_{2,eff}=-I_1+I_2-I_3\end{equation}$$ $I_1$ and $I_3$ appear with positive sign in the above equation because $I_2$ points towards node $v_4$, just like $I_{2,eff}$. $I_1$ and $I_3$ appear with negative sign because they point towards node $v_3$ while $I_{2,eff}$ points towards node $v_4$. Also, if we kept current source $I_3$, we had to replace its value with $$\begin{equation}I_{3,eff}=I_1-I_2+I_3\end{equation}$$

-

Combining voltage sources (analytical)

Circuit with 2 voltage sources, V0 (analytical)

Circuit with 3 voltage sources, V0 (analytical)

Circuit with 4 voltage sources, V0 (analytical)

Circuit with 5 voltage sources, V0 (analytical)

-

Combining voltage sources (numerical)

Circuit with 2 voltage sources (numerical)

Circuit with 3 voltage sources (numerical)

Circuit with 4 voltage sources (numerical)

Circuit with 5 voltage sources (numerical)

-

Combining current sources (analytical)

Circuit with 2 current sources, I0 (analytical)

Circuit with 3 current sources, I0 (analytical)

Circuit with 4 current sources, I0 (analytical)

Circuit with 5 current sources, I0 (analytical)

-

Combining current sources (numerical)

Circuit with 2 current sources (numerical)

Circuit with 3 current sources (numerical)

Circuit with 4 current sources (numerical)

Circuit with 5 current sources (numerical)

2.13 Power Dissipated

The power dissipated (also known as absorbed or consumed power) by a two-terminal component is given by

$$\begin{equation}P(t)=V(t) I(t)\end{equation}$$where voltage $V(t)$ and current $I(t)$ are shown in Fig. 2.20. Notice that we used the same sign convention for defining $V(t)$ and $I(t)$ as in Ohm's law. In general, power dissipation is time-dependent and varies with the instantaneous values of the voltage and current.

In general, the sign of the power dissipated by a component depends on the direction of current flow relative to the voltage polarity:

- If current flows from the positive terminal to the negative, it is supplying power (positive).

- If current flows from the negative terminal to the positive, it is absorbing power (negative).

In the case of resistors (that will be discussed in the next chapter), the power dissipated becomes $$\begin{equation}P(t)=R~\left[I(t)\right]^2=\frac{\left[V(t)\right]^2}{R}\end{equation}$$ where we used Ohm's law. Notice that, the power dissipated by a resistor is always non-negative (assuming that the resistance is positive). In the case of DC circuits, at steady-state, the power dissipated does not depend on time and $$\begin{equation}P=RI^2=\frac{V^2}{R}\end{equation}$$

The power dissipated by a component is measured in watts (${\class{mjunit}W}$). The name comes from the Scottish engineer James Watt (1736–1819), who made major improvements to the steam engine and helped usher in the Industrial Revolution.

Note: For the power absorbed by inductors and capacitors see Inductors and Capacitors.

2.14 Power Generated

The power generated (also known as produced power)) by a two-terminal component is defined as the negative of the power dissipated by that component

$$\begin{equation}P_g(t)=-P(t)=-V(t) I(t)\end{equation}$$where voltage $V(t)$ and current $I(t)$ are shown in Fig. 2.20.

The power generated by a component is measured in watts (${\class{mjunit}W}$).

2.15 Tellegen's Theorem

Consider an arbitrary lumped network that has $b$ branches and $n$ nodes. Suppose that to each branch we assign arbitrarily a branch potential difference $V_k(t)$ and a branch current $I_k(t)$ for $k=1,...,b$ that are measured with respect to arbitrarily picked associated reference directions. Tellegen's theorem states that $$\begin{equation}\sum_{k=1}^{b}{V_k(t) I_k(t)}=0\end{equation}$$

Tellegen's theorem can be proved using KVL and KCL and shows that the algebraic sum of the powers dissipated by an isolated electric circuit is equal to 0. In other words, the total power dissipated in a circuit is equal to the total power generated in the circuit. The theorem is a direct application of the law of conservation of energy and applies to any circuit with arbitrary elements, including linear, nonlinear, or time-varying components.

2.16 Energy Dissipated

The energy dissipated (also called absorbed or consumed) by a two terminal component from $t=0$ until $t=T$ is equal to $$\begin{equation}W(T)=\int_{0}^{T} \, V(t)I(t) \, dt\end{equation}$$

where voltage $V(t)$ and current $I(t)$ are shown in Fig. 2.21. Notice that, when we compute the power dissipated by a component, the current is defined as going from the positive to the negative terminal of the voltage definition.

At steady-state (in the case of DC circuits), the energy dissipated becomes $W=IVT$. Notice that the energy dissipated increases linearly with time.

The energy dissipated by a component is measured in joules (${\class{mjunit}J}$). The name comes from the English physicist James Prescott Joule (1818–1889), who investigated the relationship between heat, work, and mechanical energy.

Note: For the energy absorbed by (or stored in) inductors and capacitors see Inductors and Capacitors.

2.17 Energy Generated

The energy generated (also called produced) by a two terminal component is defined as the negative of the energy dissipated by that component $$\begin{equation}W_g=-W\end{equation}$$ and is also measured in joules (${\class{mjunit}J}$).

3. Simple Circuits

By simple circuits we understand those circuits that one should be able to solve relatively fast using simple circuit analysis techniques such as Ohm's law, current and voltage division, etc., without having to rely on more advanced methods such as nodal and mesh analysis. Examples of simple circuits are a battery that powers a DC motor, a few batteries in series that power a light bulb (such as a 3V-flashlight), a computer or TV that we connect to the AC power line, etc.

3.1 Ohm's Law

Ohm’s law states that the voltage across a resistor is directly proportional to the current going through the resistor. Denoting the constant of proportionality with $R$ (the resistance), one can express Ohm's law mathematically as $$\begin{equation}V=RI\end{equation}$$ or $$\begin{equation}I=\frac{V}{R}\end{equation}$$ where voltage $V$ and current $I$ are shown in Fig. 3.22. It is important to note that the value of the current calculated using Ohm’s law depends on how the voltage $V$ is defined. As shown in the figure, the current is assumed to flow from the $+$ node to the $–$ node; depending on the sign of $V$, this current can be either positive or negative.

If we introduce the conductance as the reciprocal of the resistance $G=\frac{1}{R}$, Ohm's law becomes $V=\frac{I}{G}$ or $I=GV$. (Please do not confuse conductance $G$ with gain $G$, which is a quantity that will be defined later in this webbook.)

The SI unit of resistance is ohm (${\class{mjunit}{Ω}}$). The name comes from the German physicist Georg Ohm (1789–1854), who formulated Ohm’s law, establishing the fundamental relationship between voltage, current, and resistance in an electrical circuit. The unit for conductance is siemens (${\class{mjunit}{S}}={\class{mjunit}{Ω^{-1}}}$), also known as mho (${\class{mjunit}{℧}}$).

-

Ohm's law (analytical)

Circuit with 1 resistor and 1 voltage source (analytical)

Circuit with 1 resistor and 1 current source (analytical)

Circuit with 2 resistors and 1 voltage source (analytical)

Circuit with 2 resistors and 1 current source (analytical)

-

Ohm's law (numerical)

Circuit with 2 resistors and 1 voltage source (analytical)

Circuit with 2 resistors and 1 current source (analytical)

Circuit with 1 resistor and 1 voltage source (numerical)

Circuit with 1 resistor and 1 current source (numerical)

-

Ohm's law (design)

Circuit with 1 resistor and 1 voltage source (numerical design)

Circuit with 1 resistor and 1 current source (numerical design)

Circuit with 2 resistors and 1 voltage source (numerical design)

Circuit with 2 resistors and 1 current source (numerical design)

3.2 Kirchhoff's Current Law (KCL)

Kirchhoff’s current law (KCL), also known as Kirchhoff’s first law or Kirchhoff’s junction rule, states that, for any node in an electrical circuit, the sum of currents flowing into the node is equal to the sum of currents flowing out of the node. In other words, the algebraic sum of currents at any node is zero (where we usually consider that current is signed positive if its direction is away from the node and negative if its direction is towards the node). Equivalently: $$\begin{equation}\sum_{i=1}^{n} I_i = 0\end{equation}$$ where $n$ is the total number of branches with currents flowing towards or away from the node. Notice that, in the case of time-dependent circuits, Kirchhoff’s current law holds at any moment in time and can be written as $\sum_{i=1}^{n} I_i(t) = 0$.

For instance, consider the circuit shown in Fig. 3.23. KCL, applied to the node shown in black, can be written as $$\begin{equation}I_{R_1}+I_{R_2}+I_{R_3}-I_2+I_{R_4}+I_1=0\end{equation}$$ Quite often, KCL is written in combination with Ohm's law in which case the current flowing through each resistor is expressed as the voltage across the resistor divided by the resistance.

Notice that KCL can also be written by considering that current is signed negative if its direction is away from a node and positive if its direction is towards the node. In this case, KCL becomes $$\begin{equation}-I_{R_1}-I_{R_2}-I_{R_3}+I_2-I_{R_4}-I_1=0\end{equation}$$ which is nothing else but the previous equation with all signs changed.

-

Kirchhoff's current law

Circuit with 1 resistor and 1 current source (analytical)

Circuit with 2 resistors and 1 current source (analytical)

Circuit with 1 resistor and 1 current source (numerical)

Circuit with 2 resistors and 1 current source (numerical)

Circuit with 1 resistor and 1 current source (numerical design)

Circuit with 2 resistors and 1 current source (numerical design)

3.3 Kirchhoff's Voltage Law (KVL)

Kirchhoff’s voltage law (KVL), also known as Kirchhoff’s second law or Kirchhoff’s loop rule, states that for any closed loop, the sum of the potential differences (voltages) across all components is zero: $$\begin{equation}\sum_{i=1}^{n} V_i = 0\end{equation}$$ where $n$ is the total number of voltages. Notice that, in the case of time-dependent circuits, Kirchhoff’s voltage law holds at any moment in time and can be written explicitly as $\sum_{i=1}^{n} V_i(t) = 0$.

For instance, consider the circuit shown in Fig. 3.24. If we go clockwise and add up the voltages across each component, KVL can be written as $$\begin{equation}R_1 I_0+V_2+R_2 I_0+V_3+R_5 I_0+R_4 I_0 + R_3 I_0-V_1=0\end{equation}$$ where we took the voltage of each source with positive sign if we went from the positive to the negative electrode and have applied Ohm's law when computing the voltage across each resistor. Notice that we can also write KVL by adding up the voltages going counterclockwise, in which case we have $$\begin{equation}-R_1 I_0+V_1-R_3 I_0-R_4 I_0-R_5 I_0-V_3 - R_2 I_0-V_2=0\end{equation}$$ however, the last two equations are identical if we move the terms to the right-hand side and reorder them.

If $I_0$ is taken in opposite direction (see Fig. 3.25), and we write KVL counter-clockwise, we have $$\begin{equation}R_1 I_0+V_1+R_3 I_0+R_4 I_0+R_5 I_0-V_3 + R_2 I_0-V_2=0\end{equation}$$

-

Kirchhoff's voltage law

Circuit with 1 resistor and 1 voltage source (analytical)

Circuit with 2 resistors and 1 voltage source (analytical)

Circuit with 1 resistor and 1 voltage source (numerical)

Circuit with 2 resistors and 1 voltage source (numerical)

Circuit with 1 resistor and 1 voltage source (numerical design)

Circuit with 2 resistors and 1 voltage source (numerical design)

3.4 Single Loop Circuits

Single loop circuits can usually be analyzed using Kirchhoff's voltage law (KVL) and Ohm's law. For instance, let us consider the circuit shown in Fig. 3.26, in which we need to compute current $I_0$.

Writing KVL clockwise (in the direction of current $I_0$) we have $$3I_0+5+2I_0+4+8I_0+1I_0+6I_0-7=0$$ which can be solved to obtain $$I_0= -\frac{2\ {\class{mjunit}{V}}}{20\ {\class{mjunit}{Ω}}}=-0.2\ {\class{mjunit}{A}} = -200\ {\class{mjunit}{mA}}$$

Notice that if we write KVL in opposite direction (but keet current $I_0$ as in Fig. 3.26), we would obtain the same answer for $I_0$.

-

Single loop circuits (analytical)